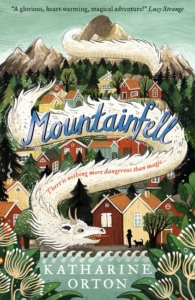

Mountainfell by Katharine Orton

Why I love writing about “complicated” characters

From Svetlana, the vengeful but conflicted sorceress in Nevertell, to the menacing yet grief-stricken Soldier in Glassheart, to all the people and forces secretly at work in Mountainfell, I love to write characters who are “complicated”.

Mountainfell follows the story of Erskin, who lives in the shadow of a dangerous, magical mountain where frightening creatures lurk. After her sister is snatched away by the fearsome cloud dragon, Erskin tears onto the mountain to try to bring her back. But on her perilous journey to the dragon’s lair, she quickly learns that things aren’t always what they seem – and the same goes for people, too.

I remember the first villain I ever truly felt for. It was Doctor Doom in an episode of Spider-Man. He told his own (harrowing) backstory, and I remember that light–bulb moment: that flicker of understanding. I still didn’t like or agree with what Doctor Doom did but … I could see why and how he’d ended up the way he had. Why he did what he did. And, looking back, perhaps I even understood what it was to be human just that little bit more, too.

Either way, my love of a complicated villain was born. I knew I wanted to write characters like Doctor Doom: characters that make you think. Characters that make you feel something for them.Sometimes we empathize the most, I think, with people’s imperfections.

Don’t get me wrong. I love a dastardly “baddie” to rail against as much as the next person. But what Doctor Doom (along with a host of other brilliant villains) taught me is that some of the best baddies are the one you feel a modicum of understanding, sympathy, even empathy for. That’s why I wanted all the characters in Mountainfell – not just the villains – to have both virtues and flaws.

As well as being brave and brilliant, Mountainfell’s main character, Erskin, fights with her sister all the time and is deeply stubborn. Fighting siblings are a reality for numerous households, and probably something a lot of children will recognize (spending time at my childminder’s house growing up, who had six sons of her own, certainly meant that I did!). But the fact that the two argue doesn’t mean one is good and the other bad; that one is entirely in the right and the other wrong… It means, more than anything, that they’re coming at things from different viewpoints, experiences and personalities.

And, as Erskin proves when she runs after her sister to rescue her, the fact that they argue doesn’t mean she wouldn’t do anything to get her back.

Characters who sometimes do things that are wrong or hurtful, even with the best of intentions, can resonate with readers’ feelings about themselves. Whether a character is supposed to be “good” or “bad”, I feel that a sprinkling of both negative and positive qualities rolled into one is more recognisably human, and often makes for a better read. More than anything, it makes characters a huge amount of fun to write, too