Can You Hear Trees Talking? by Peter Wohlleben

Peter Wollheben manages a forest academy and an environmentally friendly woodland in the Eiffel in Germany, where he leads visitors and school groups and works for the return of primeval forests. We were delighted to have the opportunity to ask Peter some questions about his book Can You Hear the Trees Talking? which is a young readers’ edition of his bestselling The Hidden Life of Trees.

Thank you for agreeing to answer some questions about your book for children Can You hear the Trees Talking? Discovering the Hidden Life of the Forest (Greystone Kids)

The intriguing title of the book begs the first question which fits nicely with National Non-Fiction November’s Communication theme. Can trees really talk?

Yes, they really can talk. However, they do not do this with sound waves, but with scent or via the roots with chemical and electrical signals. So, via the roots they are rather treemails.

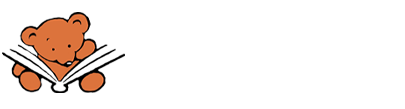

For example, a single tree notices when something bites it. After the initial shock, the tree will taste who is nibbling on it. Yes, you read that right: trees can taste. Because whenever an animal bites into the bark, a leaf, or a branch, it injects a bit of saliva into the wound. And every animal’s spit tastes different to the tree.

Right away, the tree begins to pump liquid into the bite site—liquid that tastes bad or is even poisonous. Bark beetles nibbling on the tree will often stop eating and disappear. The tree will also often release a sticky, bitter substance called pitch that the beetles get stuck in.

So that other trees can be on their guard, the attacked tree will call out, “Beetle alert!” But because it has no mouth to talk, the tree does this through the language of scent. The scent reaches the surrounding trees, so they can start producing sticky pitch even before the beetles arrive.

Some trees, such as the elm, will even call on animals for help. If caterpillars start to nibble on its leaves, an elm can tell which kind they are. So the tree calls on the enemies of these caterpillars: small wasps that lay their eggs inside the caterpillars. The eggs hatch larvae, which eat the caterpillars from the inside out. Not a pleasant thought, maybe. Still, the elm gets rid of its enemies, and its leaves stay healthy.

The book is a young readers’ edition of your best-selling book The Hidden Life of Trees. This is a two-part question: what made you decide to write a version for young readers? And was it difficult to condense and rewrite the content for a younger audience?

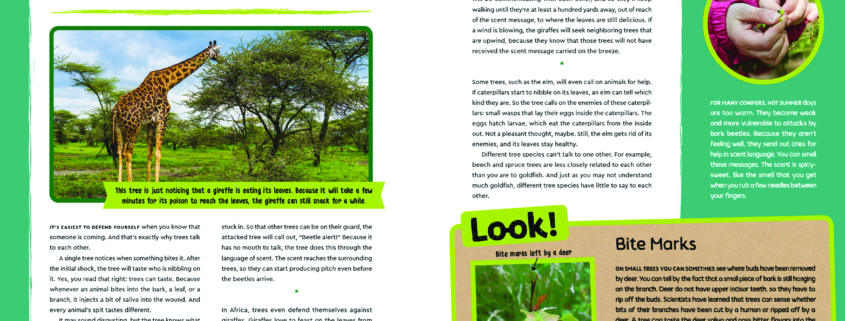

I have often been asked whether the book is also available for children. So, one day I decided to write an edition for younger readers. I’ve been leading groups of children through the forest for more than 26 years. Rather than just explain how trees communicate, live and grow, I like to really explore with the children how the forest works – for example, we look at the forest internet (there really is such a thing!) and how the trees use it to communicate. Not only that, but trees live in families, help each other out, and can even count. That sounds like a fairy tale but it’s true. The forest is exciting, and so much more than some old trees. I’ve been showing this to children in my forest school for years, so this version of my book is really a natural extension of that.

There are lots of practical activities included in this edition, so young readers can really engage with the forest, but families often tell me that adults still get lots from reading this version of the book.

Your beautiful book is illustrated entirely by photographs, which makes it unusual, as nowadays non-fiction for children tends to be illustrated by original artwork. Can you explain the thinking behind the decision to use photographs and tell us about how they were sourced and chosen?

I like both drawings and photos. In this case, I find photos important to show that this is not about fantasy figures, but about beings that really surround us every day. The photos were therefore very carefully selected to the respective text passage.

The book includes a huge range of photographs to show the forest through the seasons, up close details of leaves and branches, wider majestic landscapes, trees in the city, and also lots of the other plants, birds, animals and insects to be found within the forest.

In spite of the very attractive presentation, some people may describe the book as a bit ‘text heavy’, particularly when comparing it to other non-fiction titles aimed at 8-10s. However, it has many features designed to engage and involve the intended audience – can you describe and explain some of them?

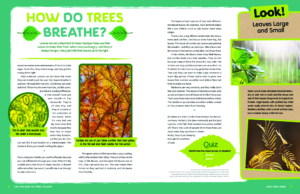

First, about the amount of text: I think it’s nice to get something out of the book for as long as possible. I wanted to include lots of information, but this is a book you can read in sections, dip into and come back for more later. For example, children can learn how to smell tree communication or feel the cooling effect of trees through double-page spreads.

The text comes in small bites with lots of side bars and information panels, plenty of striking photographs, and there are also lots of little quizzes and activities to encourage participation.

What do you hope children will gain from reading the book?

I hope that children learn what wonderful creatures trees are. What you love, you protect – and I hope for all of us that trees will be treated better in the future.

I hope that readers will see, after they have read the book and done all the activities, that the forest is always an amazing place to be. There is something new to see in the forest every single day, even for me as a forester.

Can You hear the Trees Talking? Discovering the Hidden Life of the Forest by Peter Wollheben is published by Greystone Kids, ISBN 9781771644341. www.greystonebooks.com