Real Life Snakes and Ladders by Victoria Williamson

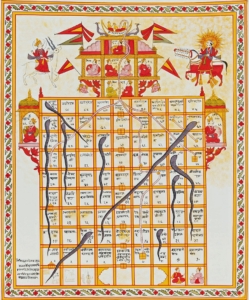

Snakes and Ladders is a board game that’s been around for a long time. The game originated in India, and is thought to have been played as early as the second century AD. The original idea of the game was that it represented a journey through life, with ladders symbolising good deeds like kindness, generosity, faith and humility, while the snakes symbolised bad deeds and vices such as anger, theft and murder. Spiritual enlightenment and salvation at the top of the board could be obtained through good deeds, while bad deeds led back to the bottom of the board and rebirth in lower forms of life. In the original game, there were more snakes than ladders, showing children that it was harder to live a moral life than one filled with vices. When the game was first introduced to England in 1892, the ladders representing a successful life continued to represent Victorian virtues such as thrift, penitence and industry, while the snakes represented indulgence, disobedience and indolence.

[Image: by Jain Miniature – http://www.herenow4u.net/index.php?id=72923, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11471979]

Snakes and Ladders continues to be one of the most popular children’s boards games to this day. I have to admit, though, when I was a child, I didn’t enjoy playing it very much. I was always annoyed by the fact that unlike other simple dice games such as Ludo and more complicated board games such as Monopoly, there was no strategy involved in Snakes and Ladders. Whether you won or lost was simply a matter of luck. When I learned later that

Snakes and Ladders was intended as a game to teach morality, this struck me as rather odd. Surely, I thought, the whole point of morality education for children is to teach them that being a moral person and living a ‘good’ life isn’t down to chance factors beyond someone’s control – such as the roll of a dice. Surely we have control over our own destinies, and we can decide for ourselves what kind of life we lead?

However, in later years as a teacher, it was brought home to me how many children’s lives and their chances of future success were down to sheer luck. Often this luck was tied to family finances. A child might love music and dream of becoming a musician, but this was a remote possibility if a free instrument and tuition weren’t available at school for them and private lessons were beyond their parents’ means. A secondary school pupil might dream of doing well in their exams and becoming a doctor, but if their family experienced homelessness and their move to temporary accommodation resulted in changing schools during an exams year, if they had caring responsibilities for another family member, or if they had no access to online learning materials during the recent pandemic, then their chances of achieving that dream became more remote.

It was this ‘luck’ aspect to life that I chose to portray in Norah’s Ark. Like a real-life game of Snakes and Ladders, eleven-year-olds Norah and Adam experience events which aren’t of their choosing, but which influence their life in many ways. Norah sees Adam as initially having many of the financial advantages she dreams of – a nice house and garden, a settled family life, and a sizable family income. She gets annoyed at Adam when he doesn’t understand how difficult it is for her father to find work when he doesn’t have any formal qualifications and he often works zeros hours contracts. When Adam naively offers to ask his own lawyer father to help find Norah’s father an office job in his company, Norah tells him:

“Not everyone did well at school and went to university! Not everyone can get nice office jobs and live in posh houses with big gardens and fancy treehouses. Not everyone has legs the length of double-decker buses and can ‘Stand Up and Stand Out’ in their expensive clothes!”

Adam at this point doesn’t see the ladders his family has had access to in life’s game of Snakes and Ladders. Norah, however, has only seen the snakes in her own life that have kept her family from climbing up the board – for example, the financial problems that have led to her and her father living in temporary accommodation and relying on foodbanks for meals. It’s only when Adam explains that he’s had leukaemia and his parents have become overprotective as a result – not allowing him to go back to school and keeping him from socialising – that she realises his lonely life isn’t perfect either. When she apologises for her assumptions, their points of view becomes more nuanced:

“Yeah,” Adam says. “But it’s fine since I’ve got a posh house with a big garden and a fancy treehouse and legs the length of a double-decker bus, so don’t feel sorry for me, OK?”

He gives me a look that says he’s kidding, and I burst out laughing. I was wrong about Adam. Our lives are totally different, but neither of them are perfect.

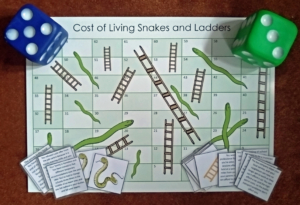

When discussing this book in schools, I use a game of ‘Cost of Living Snakes and Ladders’ to highlight some of the advantages and disadvantages that people might have in life that can help or hinder their chances of benefitting from education, getting a good job of their choice, or of becoming financially stable as adults. As teachers, parents, and members of communities, we need to do our best to ensure that children’s lives aren’t just a game of Snakes and Ladders in which their chances of achieving their hopes and dreams are out of their control and depend on the random throw of fate’s dice. We need to ensure that the government policies and social structures that we choose to put in place today give children to opportunity to make choices for themselves in future. Board games of pure chance might be fun for an afternoon, but life is a far more serious game that must be based on equal opportunities to learn and apply skills acquired through our own efforts if it’s to become truly fair.

About the Author

Victoria Williamson is an award-winning children’s author and primary school teacher from Scotland. After studying Physics at the University of Glasgow, she set out on her own real-life adventures and taught children and trained teachers in Malawi, Cameroon, and China and worked with children with additional support needs in the UK. She previously volunteered as a reading tutor with The Book Bus charity in Zambia and is now a Patron of Reading with CharChar Literacy to promote early years phonics teaching in Malawi. Victoria is passionate about creating inclusive worlds in her novels where all children can see themselves reflected. Her books have won the Bolton Children’s Fiction Award in 2020/2021, have been shortlisted for the James Reckitt Hull Children’s Book Award in 2021, the Trinity Schools Book Award in 2021, the Yaldi Glasgow School Libraries’ Book Award in 2023, and have also been longlisted for the Branford Boase Prize and Waterstones Children’s Prize.

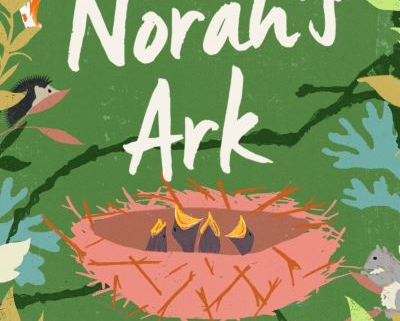

About Norah’s Ark

Norah Day lives in temporary accommodation, relies on foodbanks for dinner, and doesn’t have a mum. But she’s happy enough with her dad and a mini zoo of rescued wildlife to care for.

Adam Sinclair lives with his parents in a nice house with a private tutor and everything he could ever want. But his life isn’t perfect – far from it. He’s stuck at home recovering from cancer with an overprotective mum and no friends.

When a nest of baby birds brings them together as an animal rescue team, Adam and Norah discover they’re not so different after all. Can they solve the mystery of Norah’s missing mother together? And can their teamwork save their zoo of rescued animals from the rising flood? For more information, visit https://neemtreepress.com/book/norahs-ark/

Views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Federation.