Sail Away in a Story by A. Connors

We have a brilliant blog this morning from A. Connors all about his YA debut, a terrifying and thrilling story set in the depths of the ocean. A. Connors regales us with the ideas behind this story.

Sail Away In A Story

A. Connors

Sail away in a story… What a lovely turn of phrase! The mind fills with images of white-tipped waves lapping against the side of a sleek yacht, the smell of salt and weathered rope, a polished wooden deck dotted with plush lounge chairs. And you, reclining in one of those lounge chairs, with your favourite book in one hand and an ice cold drink in the other.

We love the sea, or we like to think we do. We love its gentle undulations, its colourful shoals of fish, even its sudden bouts of temper. But implicit in all of this is the sense that dry land is never too far away. Land. Home. Safety. Familiarity.

But that’s not what books are about, are they?

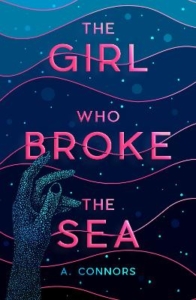

My novel, The Girl Who Broke The Sea, is set a little further out: about four thousand kilometres off the coast of Mexico, to be precise, in a region of the Pacific we call the Clarion Clipperton Fracture zone. It’s part of the Abyssal Plains, vast flatlands five kilometres under the ocean surface: it’s dark, near freezing, and the weight of the ocean would turn you into a meatcloud in a second if you stepped outside.

Books like to take us away from the normal world. They like to unnerve us with undiscovered places, and thrill us with terrifying monsters. But at the same time they like to reassure us. Through our hero’s battles with untold terrors, we are reminded of our own safety: close to shore, not too far from a well-stocked fridge.

But there’s a danger here. In our desire to create an exciting, unknown world for our hero, stories can easily reinforce our prejudices against the other. They can deepen the divide between us and them.

This is particularly a problem when it comes to the deep-sea. We are, after all, land-dwelling mammals. Our anthropocentric bias is baked so deeply into us we’re hardly aware of it. The sight of a rolling field, a snow-capped mountain, or even the Earth from space, stirs something primal inside us. But try to imagine the vast depths of the deep ocean and our imagination – and our empathy – dries up (no pun intended).

It’s a frequent lament of the ocean scientists I spoke to as part of researching my book that people don’t pay enough attention to the deep-sea. The sea contains (by some estimates) nearly 80% of all animal life on the planet, and the field of deep-sea science is so nascent that the people who work down there will readily tell you that they discover something entirely new to science every time they look. And yet we don’t think, talk, or write about the deep-sea nearly as much as we think, talk, or write about, for example … space. And when we do write about it, we don’t write about a place of wonder and discovery. We write about darkness, and giant-toothed monsters that need to be battled, and tentacles that absolutely, positively have to be lopped off.

I knew early on that I didn’t want my main character, Lily, to find a big-toothed, tentacle-wielding monster at the bottom of the ocean, defeat it, and return home. I wanted to capture something of the wonder of the deep-sea, the sense that down there we are the aliens, and the graceful, gelatinous creatures that live down there are our kind hosts. The rig in my story is called Deephaven for a reason. I wanted the loneliness of the deep ocean to reflect Lily’s loneliness. I wanted it to be a place of emotional discovery and connection. I wanted her to find self-acceptance down there, and with it, a new home.

I think this makes it a better story. But it’s important as well, because (as with everywhere else on the planet) the deep-sea is under threat and needs more of our attention and empathy. The Abyssal Plains contain vast deposits of polymetallic nodules — potato-sized lumps of copper, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. These are exactly the metals we need to build the generators and batteries that’ll help us move to a decarbonised future, and the mining companies are exerting intense pressure on the International Seabed Authority to allow commercial mining of the seabed to begin — if they get their way, by as early as this summer.

It’s a particularly interesting environmental debate, because the too-easy answer of “just don’t” is insufficient in this case. If we’re serious about decarbonising our economy (and we have to be, because we can’t ignore climate change) then by some estimates we’re going to need more metal in the next ten years than we’ve used in the entire history of humanity up to this point. That metal needs to come from somewhere, and surface-based mining is not without its own environmental and social consequences. On the other hand, the science of the deep-sea is so new, and deep-sea mining so potentially destructive, that there’s a very real possibility that if we allow industry to move too fast, if it becomes a gold-rush, we could destroy entire ecosystems before we even know they exist.

It’s a ferociously complex topic, where science, industry, and international law have been pitched into a three-way tussle. As an outsider, it’s difficult to know what to do, or whether to care. But I think this is exactly where fiction (as a medium for asking questions rather than giving answers) has its place.

Climate fiction has become a thing in recent years. It’s easy to talk about raising awareness and alerting people to impending environmental catastrophe, but I think there is much more to it than that. Books have a way of directing our attention towards the things that really matter, the things that are nourishing, and important in the world. They have a way of changing the way we think — maybe not all at once, but incrementally, in aggregate, over a period of many books, each one building on the last and influencing the next.

Right now the deep-sea is primarily associated with fear. And humans are predisposed to connect emotionally with things they can see and touch and smell on land. So how can we expect people to engage in a nuanced scientific and legal debate taking place at the bottom of the ocean?

I hope, maybe a little, by writing a book where the deep-sea is a place of emotional discovery and connection, rather than a place that is filled with monsters to be defeated.

So, sure, let’s sail away together… But remember: You’ll never cross the ocean unless you have the courage to lose sight of the shore.

The Girl Who Broke the Sea is published by Scholastic and is available now.

Views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the Federation.