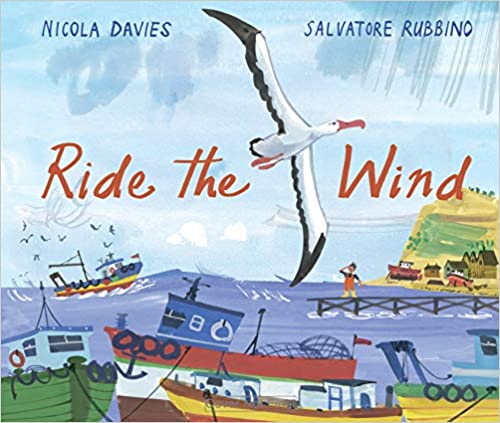

Ride the Wind

by Nicola Davies,

I was a geeky shy kid and when I went to secondary school I didn’t fit in. I concentrated on keeping my head down to keep the teasing to a minimum. But sometime in that first term, everyone had to do a talk in front of the class. My chosen subject was extinction and, as I was at that time determined to be an ornithologist ‘when I grew up’, my talk was illustrated with bird examples.

I was very nervous and I probably mumbled my way through Californian condors, passenger pigeons and great auks. I warmed up a bit on kakapos and pink pigeons but when I got to albatrosses, something in the thought of those long wings made me forget my nerves. For the first time in my life I experienced the story teller’s buzz of having an audience held in the palm of your hand. But the greatest formative power of that experience was that I was telling my classmates the best stories, true ones about some of the most wonderful creatures that evolution has ever come up with.

Albatross are simply magical. My favourites, the so called Great albatrosses like the Wandering and the Royal, are vast birds with wingspans of up to three and a half metres. Just think about that for a minute. Measure it out, and imagine wings like that spreading. They are quite narrow and pointed, specialist wings for dynamic soaring, gaining height into the wind then gliding down, to repeat the climb and slide over and over again. Wings like that are shaped for strong wind and lots of it, the sort of conditions that are routine down at the bottom end of our planet in the Southern Ocean and which none but the unluckiest of round the world sailors ever experience.

Back when I was a kid, science was only just starting to guess at the astonishing distances those wings could carry their owners. Now, radio tagging shows that they can fly for ten thousand miles without flapping once and reach speeds of almost 70 kph. Covering those kind of distances with that little energy expenditure is essential where food is scarce and patchily distributed. That’s one reason why albatrosses live so long – 50 or 60 years – and rear just one chick at a time. As with many sea birds it takes two parents to raise a youngster and the work must be evenly divided, one parent minding the baby while the other finds food, or both searching for food in different areas to ensure there’ll be enough to get their youngster to fledging. Cooperation like that requires albatrosses to choose their mates with care and court them long and thoroughly. Choosing may take several seasons and once they mate, it is til death do us part.

Sadly, for many albatrosses that comes all too soon, when one or other partner gets snagged on fishing lines whilst trying to get an easy meal from baited hooks. Much of the fish that ends up on the plates of us landlubbers comes from this so called long line fishery where thousands of baited hooks on lines miles long are dropped into the world’s oceans. Albatross are not being lazy or criminal in doing this, like the fishermen themselves, they are merely trying to survive. Hundreds of thousands of seabirds, mostly albatrosses, die this way every year and their populations are leaking adults too quick for youngsters to replace them. Mitigation is possible – lines can be set at night, streamers and weights used to deter the birds from getting the hooks. But there’s no one watching boats far out at sea and few boats adopt these measures.

Marry all that with the effects of pollution, causing adult albatross to return to hungry chicks with bellies full of squid-resembling-plastic rather than food, and you have 15 of the 22 albatross species on a collision course with extinction.

I’d kept a photo of displaying wandering albatrosses on or near my desk for more than a quarter of a century but never written about them. Then my daughter was travelling in Chile and when I googled where she was, I found fishing villages and long line boats who fish the Humbolt current, right where wanderering albatross too search for food. These small fishers, whose lives are hard as those of the seabirds catch birds by mistake and drown them, just as the big commercial boats do.

That made the first link between human and bird stories in my head, but there were others: many South and Central American people, like the albatrosses, have to travel far from home to make a living. Families are divided, and some are never reunited. At the time I was writing Ride the Wind, two close friends had children wandering the world, crossing oceans. I think our longing for our wandering offspring made me feel the story of the separated albatross pair more keenly, and helped me to make the emotional link between the human family in the story, and the albatross.

I saw this story so clearly in my head as I was writing but that’s always a risk when you are writing a picture book. It’s often better to keep the image in your head quite blurred, because an illustrator may not see it as you do. Luckily Salvatore Rubbino is not only an artist, but a mind reader. His beautiful pictures and the clear palette that he used, captured the Chilean light and the mixture of homely-ness and wildness in the bird, just as I imagined.

Nicola Davies

Ride the Wind is a story. Its characters and plot are made up. But they are rooted in reality, in the tough lives of birds and fishermen who make their living from the ocean, in the experiences of people and of birds who must be separated from their loved ones. I’m hoping the story will encourage people to think about the sea food on their plates, where it comes from and the cost to humans and the planet to put it there. We all need to think deeper and feel more compassion, for our hard pressed fellow humans and for the other non human inhabitants of our planet who have lives and loves, just as we do.

If you’d like to find out more about Albatrosses the threats they face and what is being done to help you can follow these links:

https://www.birdlife.org/news/tag/albatross-task-force

Ride the Wind is published by Walker Books and celebrates publication on 6th August 2020.

Any views or opinions expressed may not truly reflect those of the FCBG.

Thank you for a really interesting and thought-provoking article.