The Klaus Flugge Prize – interviews with this year’s shortlisted illustrators

The Klaus Flugge Prize – interviews with this year’s shortlisted illustrators

This is the tenth year of the Klaus Flugge Prize. It was established in 2016 to honour Klaus Flugge, founder of Andersen Press and a leading light in the world of children’s publishing and illustration. The £5,000 prize is awarded to the most promising and exciting newcomer to children’s picture book illustration. It is the only prize specifically to recognise a published picture book by a debut illustrator.

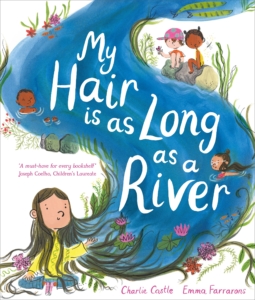

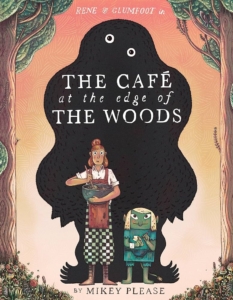

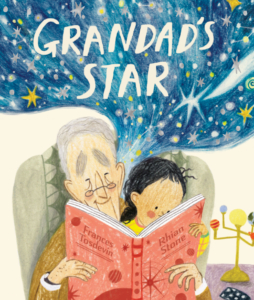

From a longlist of 15 picture books by debut illustrators, this year’s panel of judges chose three to shortlist: Emma Farrarons for My Hair is as Long as a River, written by Charlie Castle and published by Macmillan Children’s Books; Mikey Please for The Café at the Edge of the Woods, published by HarperCollins Children’s Books; and Grandad’s Star by Rhian Stone, written by Frances Tosdevin and published by Rocket Bird Books.

Find out more about their books in these special interviews!!

Emma Farrarons, how does it feel being on the shortlist for the Klaus Flugge Prize?

It’s incredibly uplifting and encouraging.

I left my job as a book designer during the pandemic to pursue my dream of becoming a picture book illustrator. Starting from scratch, finding my voice, and now having my debut book shortlisted—it honestly feels like a dream come true. I’ve followed the prize for years as a designer, so it’s a real honour to be in the company of so many illustrators I admire.

The judges said: “The illustrators they have chosen to shortlist have very different styles and subject matter but share an exceptional ability to tell a story and to create mood and character, while their originality and talent stood out.” How does that comment add to your emotional reaction to the announcement?

I love that this prize celebrates such a wide range of styles and approaches. There’s no single way to be a picture book illustrator—every voice and visual language has value.

To be recognised specifically for storytelling, mood, and character is especially meaningful. As this was my first book, there were so many moments when I felt like a rabbit in the headlights—unsure of what I was doing. My designer Lorna and editor Grace at Macmillan Children’s Books were incredibly important in helping me shape the pacing, mood, and character. They pushed me in all the right ways. It was true teamwork.

What do you hope readers will take from reading your book?

When I first read Charlie Castle’s manuscript, I got goosebumps. It felt like an invitation to step into the imagination of a very special little boy—and I wanted to honour that.

I hope readers feel empowered to be exactly who they are, just as they are. I also hope it encourages them to stay open and curious—about others, and about the world around them.

Interestingly, after I finished illustrating the book, my own little boy decided to grow his hair long—something he’s now really proud of.

Ultimately, I hope this book sparks children’s imaginations. I want it to invite them to dream big, get lost in play, and feel brave enough to create their own worlds.

When did you discover your talent for illustration?

Pencil and paper were always my favourite toys growing up. I studied illustration back in 2000, but at the time my focus was completely different—I was more interested in design elements like typography, lettering, bookbinding, and black-and-white line work.

That path led me into a career in children’s book design, where I worked closely with illustrators and quietly admired what they did. But I wasn’t there yet—I hadn’t found my voice as an illustrator.

Then in 2018, I had a moment of clarity: I didn’t just want to design picture books—I wanted to illustrate them. But I quickly realised how much I had to learn. I didn’t know how to draw emotion, or people doing things from different angles. Creating full-colour scenes and telling a story through images felt completely out of reach. I had no idea where to start.

That’s when I reached out to the team at Orange Beak Studio. Their advice was simple but powerful: spend a year drawing only from life. No photos. No copying other artists. Just observe the world and draw every day. Try new materials and see how they behave. Play. Make mistakes. Study perspective, anatomy, tone. Really look, don’t just see.

I took this advice to heart. I drew every day for two years—on trains, in playgrounds, during lunch breaks, at the barbers, even the contents of my kitchen cupboard. Anything and everything. It helped me rebuild my drawing voice from the ground up.

Then one day, observational drawing became a bridge—between drawing from memory and inventing from imagination. That’s the day I felt like I’d truly found my voice in illustration.

How long did this book take you to illustrate?

It took a full year. The biggest challenge was working in full colour, using materials I wasn’t familiar with.

My comfort zone is black and white—playing with tone, mark-making, and a range of grey values. That’s something I developed through observational drawing, so the black-and-white roughs came fairly naturally.

But full-colour scenes were a whole different story. This book is about a boy with a huge imagination, so the illustrations needed to feel alive—bursting with colour, energy, and emotion. That meant pushing myself far out of my comfort zone. The idea of working in bold, expressive colour was both terrifying and exciting. It was a steep learning curve, but my editor and designer gave me time and space to experiment.

I started with a small collection of materials—coloured pencils, gouache, watercolour, acrylics, inks, brushes, papers—and spent an hour a day just playing with colour. Studying colour theory. Trying things. Failing. Trying again. Gradually, I started to figure out what worked—what felt right for skin tones, flowing hair, limpid pools, crashing waves, rocky cliffs, tangled vegetation.

In the end, I found a mix of materials that felt right: Daniel Smith watercolours for their richness and granulation, Golden acrylics for vibrant colour and fast drying, liquid graphite for shading, and a dip pen with ink for loose, energetic line work.

One of the best things I did was join illustration prompts on Instagram, like the Imaginary Book Cover challenge. They gave me pressure-free practice painting full-colour scenes.

There was a lot of time spent on research as well. All my references came straight from life—through my sketchbooks. I drew children in playgrounds, plants and flowers in Peckham Rye, trees in Sydenham Woods. The waterfalls, waves, and dramatic landscapes came from family holidays in Cornwall. Even my local library in East Dulwich appears in the book—it’s in the opening and closing scenes.

Another big challenge was learning to stay loose. It’s so tempting to tighten up in final artwork, but my editor and designer were brilliant at nudging me back to my sketchbooks—to keep that spontaneous, playful energy in the line work.

Honestly, it felt like a baptism of fire—but in the best possible way. And in the end, despite all the trial and error, it was a lot of fun. It felt like a year of pure play.

Mikey, how does it feel being on the shortlist for the Klaus Flugge Prize?

It’s a great honour to have The Café at The Edge of the Woods picked out during what must surely be a golden age for picture books. There are so many fabulous books that I am never short of flabbergasted by the talent on display on the local bookshop shelves. I’m holding my breath, waiting for the note that politely lets me know there’s sadly been a clerical error.

What do you hope readers will take from reading your book?

I’m a big believer in letting people see what they want to see in a story. If I sit down to enjoy a story and come away with a moral lesson, I can’t help but feel slightly cheated. That said, right after people appreciate the tenacity it takes to realise your dreams, and how perfection needs compromise, how fun it is to rearrange food to look like silly things, I hope people recognise the theme of the power of the peacemaker. To stand between two parties with conflicting ideas and pull them together is a skill we sorely need more of.

When did you discover your talent for illustration?

Hmm, interesting question. I wrote a very long, and slightly pompous answer about how I don’t really believe in ‘talent’, which I will be happy to discuss one day in person over a glass of wine. But for the purpose here of a light-hearted interview, I shall answer the slightly different question of ‘when did I get into illustration?’

My background is in animation, so, though I have spent most of my days writing and drawing for a living, the requirement to actually produce a finished illustration is completely new to me, and this book represents my first attempt at it.

How long did this book take you to illustrate?

I spent about 6 months chewing over the poem, reading it to my kids, my friends and family and gauging their reactions. Seeing where they laughed, where they wanted to edge away from me. Then I spent a summer filling a sketchbook with explorations of the world, figuring out who these characters were, where they lived, and the rough beats of how the story might be told. The roughs came together relatively quickly, and I had the arrogant assumption that the final drawings wouldn’t be much more effort. Oh, how wrong I was. I was truly floored by how much time and energy it takes to have an image hold up, and carry the weight of a story all in a single snapshot. I don’t know how long exactly that final art pass took me, but I’ll say it was much, much longer than I had expected or scheduled for.

Rhian, how does it feel being on the shortlist for the Klaus Flugge Prize?

I’m delighted, humbled and very surprised to have been shortlisted, especially alongside such talented illustrators as Emma Farrarons and Mikey Please.

“The illustrators they have chosen to shortlist have very different styles and subject matter but share exceptional ability to tell a story and to create mood and character, while their originality and talent stood out.”- this comment is taken from the press release and highlights the array of talent honoured by the award this year- how does this comment add to your emotional reaction to the announcement?

It’s very, very lovely. When you’re working on a book, there’s a lot to consider, a lot to get “right”. For me, trying to get an image out of my head and onto the page is like looking at an object through the wrong spectacles, so to get these kinds of comments is incredibly reassuring and validating.

What do you hope readers will take from reading your book?

I hope that they will feel comforted and moved by Frances Tosdevin’s tender and delicate words, and I hope they will enjoy looking at the pictures.

When did you discover your talent for illustration?

I have always enjoyed drawing; it’s something I’ve always done in some form or another. However, it was only in my late twenties that I realised I wanted to pursue a career in illustration. Then I had the challenge of not only rediscovering how to draw but, more importantly, how I want to draw (an ongoing debate haha).

How long did this book take you to illustrate?

I think the entire process was around nine months.

The winner of the 2025 Klaus Flugge Prize will be announced on the evening of Thursday 11 September.