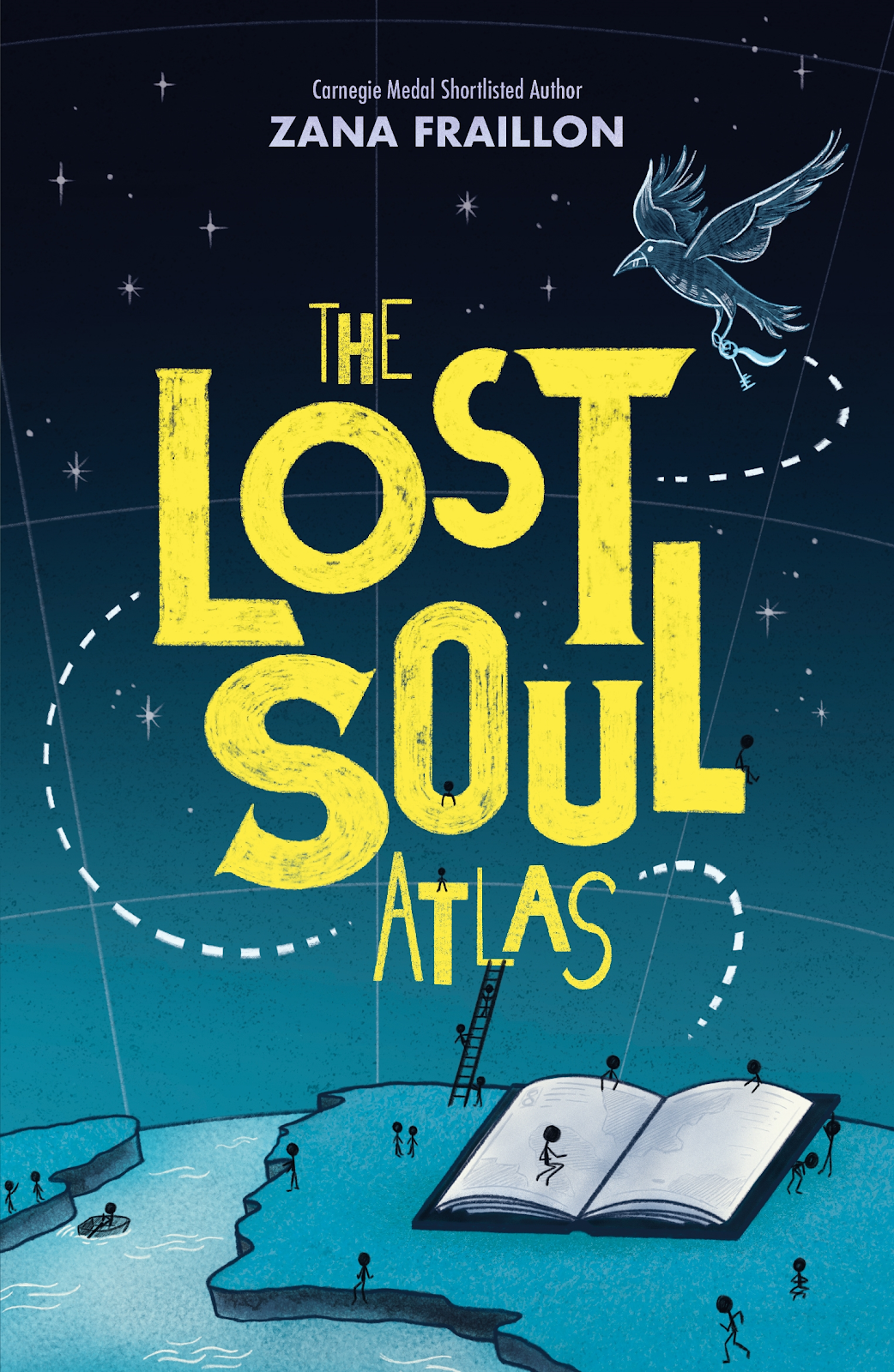

The Lost Soul Atlas

Zana Fraillon’s The Lost Soul Atlas is a magnificent tale of Twig and his quest to find his father in the Afterlife. A harrowing journey of memories, a life in tatters and a mysterious atlas guiding him. Full of rich language and vivid imagery. Twig becomes homeless and is adopted by a group of children living off the streets. Read on for an insightful guest post from Zana Fraillon.

The Lost Soul Atlas publishes on 23 July 2020 by Hachette.

Folktales have a lot to tell us. There’s an old tale, an ancient tale, that tells how on the night we are born, our twin is born too. This twin – and we all have one – is cast from our homes, out and into the wilds. And there they stay. Waiting for us to find them. Waiting for us to call them home.

I have been thinking about this tale a lot lately. As the entire world becomes more wild, more dystopian, more surreal, more folkloric every day, I have become increasingly troubled by how easily the things that hold us together, that keep us in control of our lives and our wants and our needs, can be so quickly disrupted. The world feels as though it has begun to crumble, to unspin, like the fairy tale palace held up by dreams. It feels more and more as though we have become that secret twin, cast out into the unknown.

None of us are in control any more. All of those safety nets, those laws written to protect us, our contracts, our assurances, our belief in ‘the system’, all of our well-made plans have vanished. In the space of a few weeks, so many of us have found ourselves unable to work, out of work, unable to pay bills, rent and mortgages, unable to care for family, struggling every day, every hour, every minute with anxieties and an increasing number of mental health issues. Each night I wish for a dreamless sleep. Each morning I wake with an aching jaw. My gums bleed from the constant clenching.

The streets too, have become storied. With people confined to their houses, the cities have become ghost towns. Stuck in time and waiting. We look at each other in bewilderment and bemusement. How can this be happening? We had things planned. ‘This year is a dead year,’ my son announces, and my other son muses that perhaps it will be more than a year … My hopes for the foreseeable future shrivel. Each day feels harder to begin. Who can feel enthusiastic about the day ahead when all the days run into each other, one after the other, with moments of joy, yes – but all so very much the same? Police, with their increased powers and a sudden over enthusiasm with fining people for being out without cause, have become figures of fear . I find myself freezing when I see their uniforms and try to hide this response from my children. I look upon other people on the street with suspicion – what are they doing out? That doesn’t look essential. And surely that group isn’t all from one family? The world unspins just a little more …

None of us like this new world order. None of us feel safe or secure. We are unhinged. And yet, for so many of us, for too many of us, all of this is nothing new – this unspun world was already the norm, long before a pandemic was ever declared. The derailment of the everyday, the loss of control, the spiral into a nonsensical world, the lack of security, the lack of safety, the endless days, the constant struggle with mental health, the fear of the police, the lack of employment opportunities, the inability to pay bills or rent, the inability to buy food. The loss of hope. This year is a dead year. But for more than 320,000 people in the UK, 116,000 people in Australia and 553,000 people in the United States alone, this year is every year.

Homelessness is an issue that affects every single country in the world, and yet, people experiencing homelessness are perhaps the most invisible members of our community. As Gregory P Smith writes, ‘to be homeless is to be seen through … the vast majority of passersby pretend that the unfortunate soul on the park bench or huddled on the inner-city footpath in front of them simply isn’t there. They’d look right through me as if I was made of glass.’ Not any more. Now, perhaps because the streets are so empty, or perhaps because of our heightened sense of threat to our own health, people who have no home to isolate in, no supply of hand sanitiser or masks or sinks or soap, are suddenly being noticed.

It takes a pandemic for the homeless to be seen. ‘Stay at home! Save lives!’ ‘Wash your hands!’ Some of us have no choice. Headlines such as ‘Homelessness and overcrowding expose us all to coronavirus’ and ‘Coronavirus could hit the homeless hard, and that could hit everyone hard’, highlighting just how callous we have become. Cities worldwide are now addressing the issue of homelessness and putting money, time and resources into doing so – because of the risk to the wider population.

Where was this assistance when the mother of a baby desperate for housing was turned away, only to have her two-month-old son die overnight in the car? Where were the resources when a young boy, escaping domestic abuse, woke to find grown men deliberately urinating on him in the night? Where was the money for the family who survived war and persecution only to find themselves here, with no access to support systems? Where was the time given, when, on their eighteenth birthday, a foster child was forced out of the system, with nowhere to go and no one to turn to? Where was the help for the thirteen-year-old girl, working the streets simply to survive? I am reminded of the line from the poem Home by Warsan Shire – ‘No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark’ – and I wonder where the money, time and resources will be when there is no longer a perceived threat to the rest of us?

Meanwhile, in the last month, there have been a record number of calls to food relief, as more and more people are finding themselves unable to provide the basic necessities for themselves and their families. Measures such as the JobKeeper allowance are not provided to some of the most vulnerable people in our community, including refugees, asylum seekers and migrant workers who now find that, despite living in the country and paying tax for years, they will not be supported in this time of crisis. More and more people are now finding themselves without a home.

Each day we watch for a flattening of the curve in the coronavirus graphs. Meanwhile, the graphs showing rates of homelessness are only getting steeper. Thousands of people without a home die each year in the UK and Australia from causes exacerbated by homelessness. The average life expectancy for someone experiencing chronic homelessness is forty-seven years old. And while rumours of toilet paper shortages saw people fighting each other in the aisles and hoarding resources until our supermarket shelves were empty, the result is that those supermarkets who donated goods to the homeless are now unable to donate. Instead, they need all of their stock to replenish the shelves and keep up with increased consumer demand, so that those of us with enough money to do so can continue to fill our pantries and freezers to the brim. And while we can convince ourselves that we are simply being prepared, being responsible parents, that we are looking after our own camps and our own nests ‘just in case’, it is young people no different to our own children who are suffering because of it. Worldwide, it is estimated that there are up to 150 million children who are currently living on the streets. This is more than the entire populations of the UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and Greece combined. In Australia alone, more than 19,000 children under the age of fourteen were homeless on census night. The number of young people experiencing homelessness in the UK is estimated to be 86,000 … It is these children, these thousands of children, who are now at an increased risk because of our fear of not having enough toilet paper.

Folktales have a lot to tell us. Folklorist Martin Shaw writes that to find our wild twin, to bring them home, is our life’s goal – to seek out the estranged, exiled self that we have shunned and ignored and to invite them back into our consciousness. It strikes me that all of those millions of people experiencing homelessness in our towns, our cities, our countries, they are our secret twins, cast from our homes, sent out and into the wilds on the night we were born. They are us. Look where we are now. All of us. Look how swiftly and easily we fell. We are no different to the woman wrapped tight with newspaper for warmth, or the man asleep on the cardboard box. Our children are those children sitting at train stations, sniffing glue and petrol, trying to forget. Those children who will die, from hunger, from sickness, from cold or heat, from drug use. Our children are those children, vulnerable, scared and alone on the streets.

If this pandemic has resulted in anything positive, it has forced us to see the invisible. To notice those we wished to forget, to walk past, to ignore. There is no more pretending that we do not know. Just like the old tales, once you have had fairy dust rubbed in your eyes, you are destined to forever see.

So when we come out of this dystopian world, when the cities are no longer ghost towns, when those of us that are lucky enough are able to go to work and school again, to picnic in parks and playgrounds, when we are given back our sense of order over our own lives, will we remember how easy it was to lose it all? No one leaves home unless …

Any views expressed may not truly represent those of the FCBG.

A beautifully written and achingly honest view of what is happening in our world today Zana. Let’s hope your book will inspire us to find our twin and help bring them home.

I love this blog – it is so well written and thought provoking. Would you consider allowing it to be re-published in Primary Matters, the NATE magazine for primary members? Please get in touch with me if you would.